Continuous Improvement

12 min read

Firefighting In Manufacturing

Why It Happens, What It Costs, and How To Stop It

Firefighting is a burning issue in manufacturing.

Not only are facilities dealing with safety measures like flammable materials, autoignition temperatures, flame propagation rates and extinguishing devices.

There’s also the other kind of firefighting that’s just as dangerous.

Managers and supervisors spend so much time and effort dealing with problems that need attention immediately, that they won’t have any time to:

-

Improve the standards

-

Upskill their workforce

-

Capture and transfer valuable knowledge

-

Empower their workers

-

Reduce downtime

-

Increase productivity

People are too busy being reactive. Trying to rework their scrap list, understand all their outdated work instructions, track employee training, organize production plans and so on.

Unfortunately, firefighting has become so embedded as part of the manufacturing culture, that it rarely gets discussed. Or if it does, the wrong questions are asked. Rather than reacting with, “How do we fix this problem?” teams should take a step back and wonder:

“Why has this problem happened? How can we prevent it from happening again?”

The same patterns around firefighting seem to repeat themselves. Let’s unpack why firefighting happens, what it costs manufacturers, and how leaders can approach problems from a more strategic, intentional and profitable perspective.

Why Firefighting Happens

To begin, here’s a linear explanation of what forces and moments cause firefighting in manufacturing:

-

Companies don’t create the standard and train frontline teams around it

-

Management announces that they have found the best (and sometimes the only) way that they’re going to do things

-

One veteran operator at the plant, who knows how to run a machine really well, has their own process for how they do it

-

The organization becomes heavily reliant on those types of people, so when the line goes down for a few hours, they call that particular expert

-

She comes in off-shift to fix the problem and save the day, where she is celebrated for her heroic effort

You would be shocked how common this is in manufacturing.

Heroic efforts are commonplace in factories.

Companies often rely on the most experienced and knowledgeable employees to save the day, while overlooking the reality that firefighting is often the result of worker error. Someone made a mistake because they weren't trained well or didn't have access to work guidance at their time of need.

Not to downplay people’s meaningful contribution. Everyone loves a hero at work, and being one is professionally fulfilling. It’s just that this process fails to go back and dig into the root cause. Manufacturers never get off the firefighting treadmill.

The smarter, leaner and more scalable approach is to train everybody to be able to operate machines the same way. To get everyone aligned on the organizational definition of what the best practice is. That way, you get the same outcome every time.

Without an intentional and organized approach, the debris and collateral damage of these fires pile up quickly. Especially the costs.

What Firefighting Costs Manufacturers

Now that you understand why firefighting happens, here’s a hypothetical use case on what the potential cost of that habit is:

Imagine an automotive parts manufacturer who has to hit their production target of two hundred brake pads. They’re behind a hundred widgets, so the supervisor tells the frontline team to kick it into gear and do two hundred more. Naturally, their team works hard, fast and heroically. They end up exceeding their goal by fifty percent, so the plant manager begins celebrating the team for surpassing their standard number.

This might not be the best achievement to celebrate. Don’t crack the champagne just yet.

Facilities really should be hitting their exact number each day so there are no supply chain constraints or material flow issues. If the raw materials components coming in at the normal pace don’t match output, that could be trouble.

This overproduction can start a number of fires that cost time, money and energy to put out:

-

Human resources incur the waste of overstaffing

-

Managers struggle to plan out how much supply is needed

-

Unnecessary storage and transportation costs to handle excess inventory

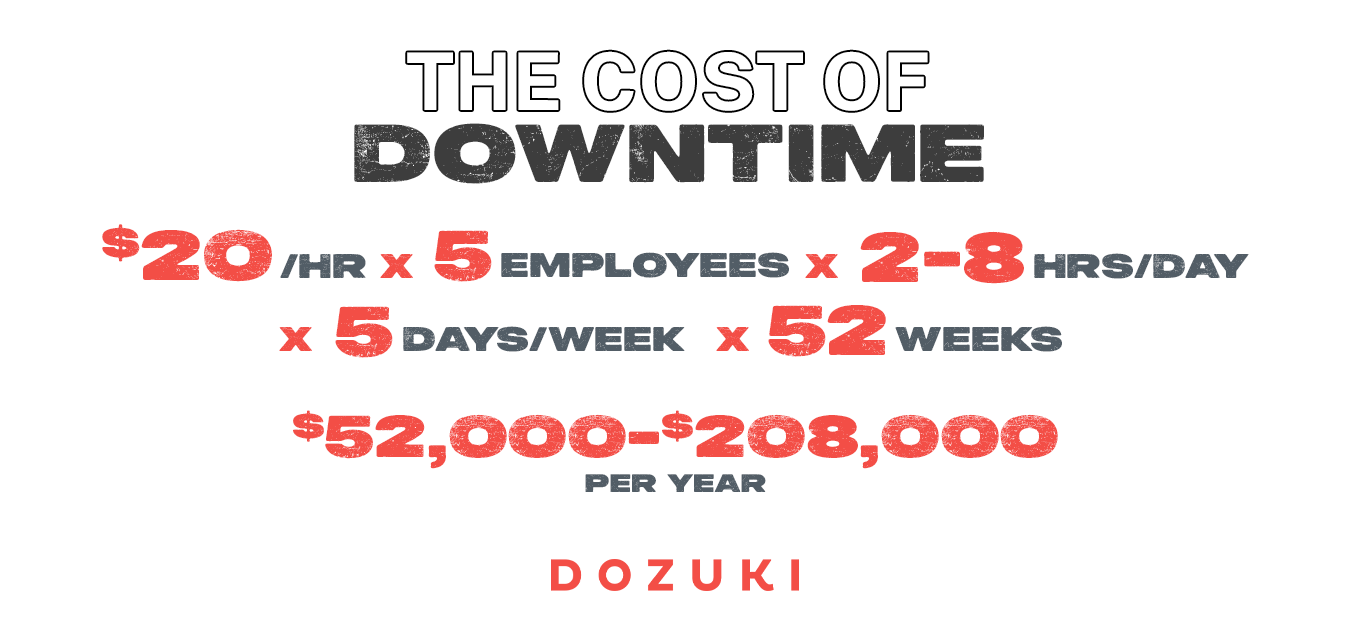

Here’s a case study that astonished us a few years ago. Our longtime customer, a large construction equipment manufacturing company, struggled with the habit of firefighting. Their head of operations showed us the math about how much unplanned downtime costs their team from a labor standpoint.

“Our previous checklist was pencil whipped (aka, approved carelessly without supporting data or evidence) by five employees on the line. This caused two to eight hours of machine downtime every other day. At an average pay rate of $20 per hour for five line employees, the cost of downtime was $1,200 per week or approximately $62,000 per year. And this total doesn’t account for the downstream employees who had to wait for the parts to be made to continue assembling.

Please note: This particular story was only for one line, of many. When that success replicated across the organization, the cost savings were profound. Dozuki has helped them save multiples of that, simply by having a documented standard to work from, ensuring that even the most inexperienced people can perform a task properly.

Today their frontline is much more diligent about documenting processes, and work is completed faster, predictably and with desirable results. And with fewer fires to fight, the team can stay focused on doing what they do best — making world class construction equipment.

Lesson learned, if a manufacturer is doing their job right, then it should not require a heroic effort from everybody. If you have to have a heroic effort to hit targets, then there’s clearly something wrong with your root processes.

It’s funny, manufacturing companies diligently pay attention to material waste, but when it comes to less concrete and exact wastes (like labor and motion waste) the attitude is much different.

“We’re behind schedule for this work order? Fine, let’s just tell the team to work another shift on Saturday.”

But with labor waste, it’s less visible, so it doesn’t get as much attention. Materials waste is a heap of broken parts and scrap material piling up in the corner of the factory. And when it comes to human effort, the variables are harder to measure.

By now, you should have an understanding of why manufacturers engage in firefighting, (either consciously or unconsciously), and what that can cost your operation. Our final section will be recommendations on how to nip this costly habit in the bud.

Resigning Your Post as Chief Arsonist

Below are several strategic and tactical recommendations that your facility can implement starting today.

-

Shift from being reactive to proactive. Whether it’s with improper changeovers, training modules, machines that throw out bearings, or delays in other projects, being reactive will always feel like death by a thousand cuts.There’s never one big manufacturing issue that’s fatal in itself. But lots of small bad things are happening, which add up to a slow and painful demise. It’s critical that team leaders start by being intentional about their Digital Transformation. Because the reality of our industry is, you can never make a better system if you're having to put out fires all day. You're always having to fix things. Hidden problems jump up and bite you in the face. And continuous improvement continues to elude you. Whereas if you decide from the get go that you’re not going to be another firefighting type of organization, you lay the groundwork for productivity and quality.

-

Make frontline training digital and diversified. Eliminating firefighting ensures that workers will be less likely to do things incorrectly. And if you use the right tools to make training engaging, seamless and scalable, then there will be no more relying on the heroic efforts of a few key people. The goal of training should be to enable anyone to fix problems that arise, and to execute work expertly. Dozuki gives you a universal repository of troubleshooting scenarios and issues that might arise for any given process, and if you build that tool into your training process (almost like an “if this, then that” structure) you can account for mistakes before harmless sparks turn into a raging flame. Documentation that people can refer to quickly and easily is literally and figuratively a lifesaver. Make it fast to access and present the material in an engaging way with visual context that aligns with how today’s professionals are accustomed to learning new things.

-

Prevent compounding problems. If there’s an issue on the line, stop production. Identify what caused it. Maybe the process issue is bad training. Or maintaining equipment improperly. Or not running it right. Or not performing frequent enough quality checks. It’s hard to tell. But if those root causes are not identified and understood, the firefighting will continue. Toyota popularized this approach to continuous improvement decades ago, and it still holds water today. And it’s understandable that frontline workers don’t want to kill the momentum of the line. Especially if the first shift of the day is entirely dedicated to startup and dialing in the machines. But there’s more important goals than always pushing to the max. Asking what the most amount of units we can produce isn’t always best for the organization. Besides, there’s usually a ten to fifteen percent buffer built into production targets, so it’s acceptable to stop midstream and fix the problem right now, rather than having two hundred products built incorrectly.

To wrap up, here’s an insight from Chad Nelson from 3M, whose interview on The Voices Of Manufacturing Podcast, was enlightening. We asked him about firefighting, and here’s what he recommended:

“The way I see it, and maybe the non traditional textbook answer is to really focus on and build process stability. And in building process stability, it helps us make abnormalities visible. And as we bring those abnormalities to light, it helps improve the capabilities of our employees and our people to help see and solve those problems in real time.

At the end of the day, I think that's really what standard work is trying to do is to create a visual workplace that allows us to see and solve problems against a no one standard or a no one way that we want the work to be done.”

Remember, if you need a heroic effort to hit targets, then there’s something wrong with your process.

Next time you’re tempted to react by fixing this problem, take a step back.

Wonder why this problem happened, and how you can prevent it from happening again.

Topic(s):

Continuous Improvement

Related Posts

View All Posts

Frontline Digital Transformation

Frontline Of The Future, Part 3

5 min read

Accessibility Creates Profitability Manufacturers that don’t provide broad access to essential knowledge are at a significant deficit. This form of content debt comes at a...

Continue Reading

Work Instructions

The Cost of Bad Work Instructions

10 min read

Bad work instructions are the norm. Documentation is often created to check a box for audit or compliance purposes. But once completed, those work instructions get trapped...

Continue Reading

Continuous Improvement

How To Increase Productivity in Manufacturing

19 min read

There are several ways to define productivity depending on the context. In terms of manufacturing, productivity relates to the speed at which quality work is performed....

Continue Reading